By Charles LaVell Scott – MArch., MBA

Abstract

El Corazón Del Oso (The Heart of the Bear) is a regenerative housing prototype that challenges the architectural norms of affordable housing by repositioning the home as an economic organism and a cultural vessel. This article introduces a radical live/work housing typology rooted in compressed earth block construction, ADA-inclusive design, and post-capitalist economic logic. It uses Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs as a spatial framework and builds a case for housing as a generator of sovereignty—financial, ecological, and existential. In doing so, the project merges architecture with agency, sustainability with symbolism, and structure with soul. El Corazón Del Oso does not merely house—it heals, employs, and remembers.

Introduction: The Architecture of Dispossession

We are living through an age of engineered instability.

As housing prices surge and wages stagnate, architectural discourse around affordability has often failed to confront the root pathology: housing is no longer designed for livability or local legacy—it is designed for extraction, speculation, and erasure. From modular prefab solutions divorced from place to soulless high-density towers that sterilize culture, architecture has become complicit in the very crisis it seeks to solve.

But what if housing could remember its role?

What if a neighborhood could hold memory like a sacred archive? What if a single building could generate wealth, healing, and belonging—not in abstract terms, but in material, daily life?

El Corazón Del Oso emerges from this inquiry. Located at the intersection of indigenous land consciousness, economic resilience, and bioregional logic, the project offers a new prototype: one where compressed earth walls breathe with the soil, where entrepreneurial space is embedded into domestic life, and where inclusivity begins at the base course of the plan.

This article presents El Corazón Del Oso not just as a housing model, but as an evolutionary architecture—a system that responds to displacement, climate trauma, and cultural loss with dignity, autonomy, and ritual.

Methodology: Designing from Maslow’s Base

To design El Corazón Del Oso is to ask:

What does a human being need—not just to survive, but to belong, to heal, to actualize?

Rather than begin with zoning envelopes or budget spreadsheets, this project begins with a psychological scaffold: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Not as a static pyramid, but as a living architecture, where each spatial element satisfies a foundational human necessity.

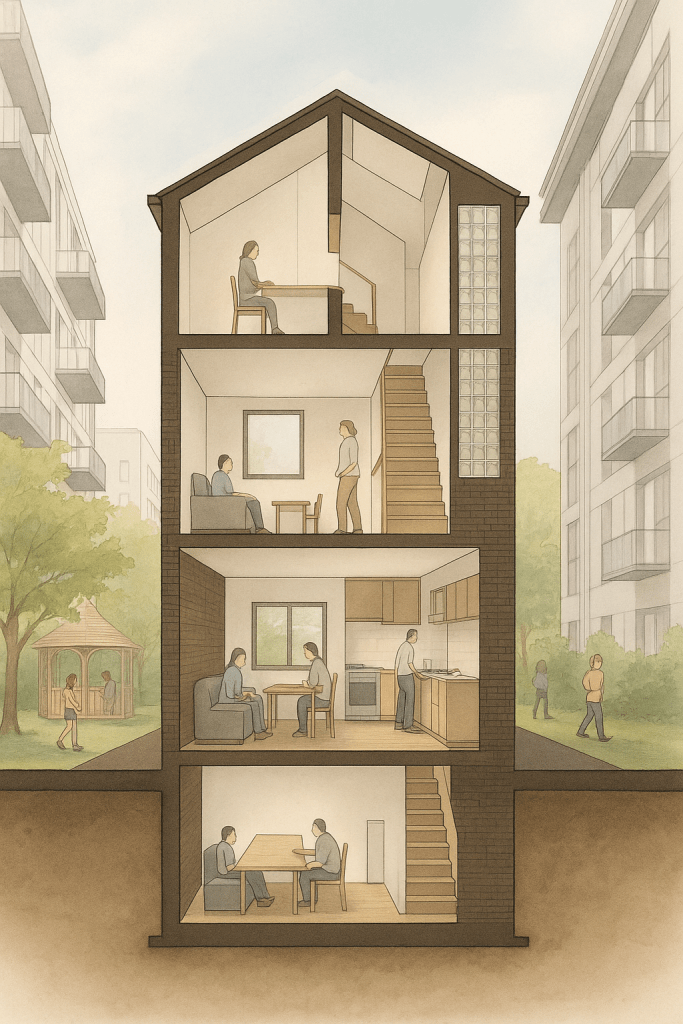

This model becomes a spatial methodology—a way of mapping psychological wholeness into physical form:

1. Physiological Needs → Shelter + Soil

The first level—food, water, rest, warmth—is translated into:

Compressed earth block construction: breathable, thermally stable, and made from the local land Greywater systems and solar energy: closed-loop resource use Integrated garden zones: passive food production and medicinal planting

Here, the walls literally come from the land beneath one’s feet. The home becomes a womb of stability, grounding the resident in ecology and permanence.

2. Safety Needs → Ownership + Access

The second level demands stability, protection, and order. It’s met by:

Live/work configurations: Each unit contains space for enterprise—barbershop, herbalist, counselor, etc.—generating household income Inclusion of ADA units by design: Not an afterthought, but a structural principle High thermal mass + stormwater control: Climate resilience as built-in safety Legal structure of ownership: Affordable pricing with pathways to equity

Here, architecture becomes a financial shelter as much as a physical one.

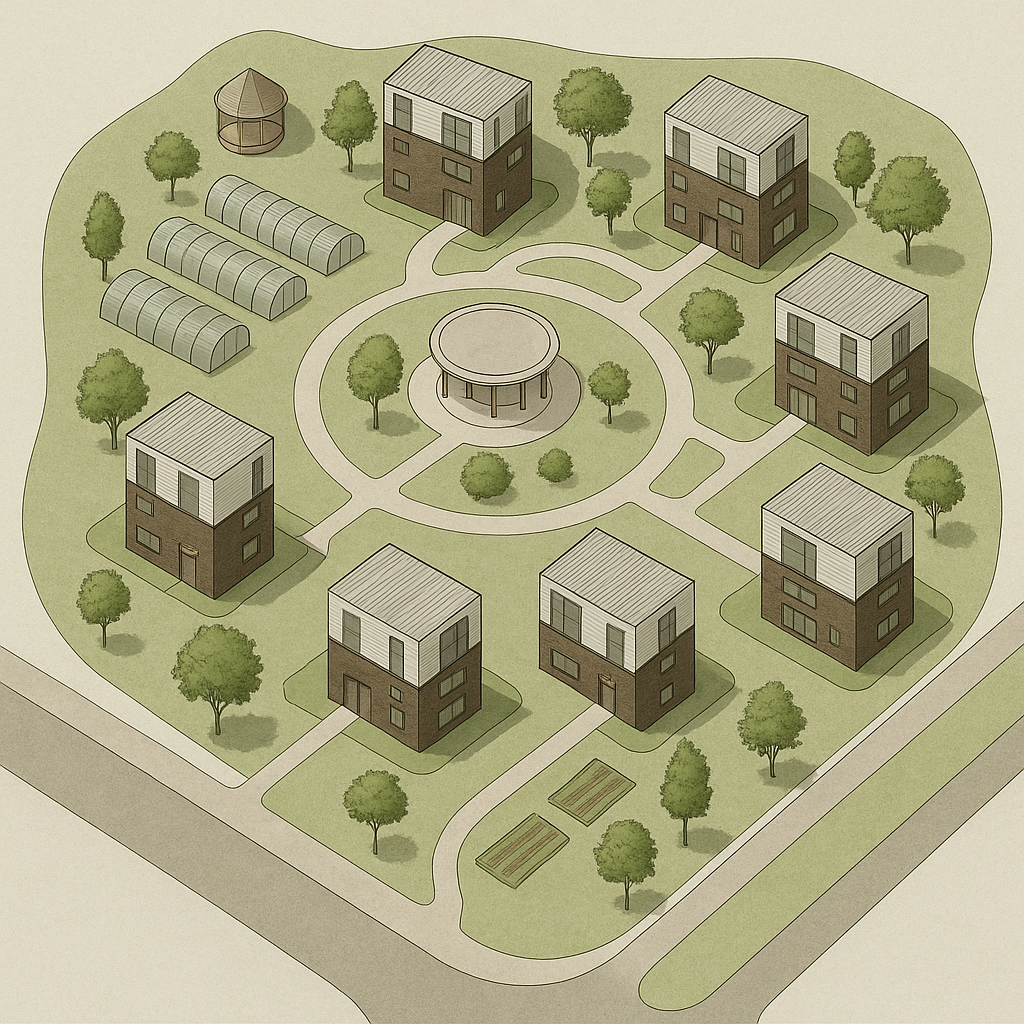

3. Belonging Needs → Communal Ritual Space

The third level is where housing often fails: the emotional need for community and identity.

El Corazón Del Oso responds with:

Shared courtyards and ritual zones for cooking, drumming, storytelling Cultural expression in form and material—e.g., wall textures drawn from indigenous patterns Units designed to enable both privacy and porosity, reflecting kinship structures common in ancestral communities

This is not density for density’s sake. This is designed proximity—an invitation to gather.

4. Esteem Needs → Purpose + Presence

People need to feel useful, respected, and visible.

That’s why the project:

Flips zoning norms to embed economic activity into housing Uses vertical rhythm and staggered massing to give each unit architectural presence Integrates signage and shopfront scale into homes, creating dignified visibility Welcomes elders and youth alike as stewards of land and culture

This is not charity—it is built dignity.

5. Self-Actualization → Architecture as Mirror

The final level is rarely considered in affordable housing: personal fulfillment.

El Corazón Del Oso is a canvas for becoming. It allows its residents to:

Shape their economic destiny Interact with sacred ecology Participate in a spatial story larger than themselves

By rooting architectural decisions in Maslow’s framework, the project becomes not just structurally sound—but spiritually intelligent.

El Corazón Del Oso: Spatial Strategies of Empowerment

Where conventional housing typologies prioritize efficiency, El Corazón Del Oso prioritizes sovereignty. Every material, massing move, and circulation path is selected not to maximize units per acre, but to maximize autonomy per life. The architecture becomes a toolkit for empowerment—economic, ecological, and cultural.

1. The Earth as Wall and Witness

At the literal foundation of the project is compressed earth block (CEB) construction. Earth, stabilized with minimal cement, is pressed into thick structural walls that offer:

Thermal mass for passive cooling and insulation Textural depth that reflects ancestral building traditions Biophilic grounding—residents live within the earth, not just on it

CEB reduces the project’s embodied carbon while enabling hyperlocal labor training. In this way, the wall is not just structure—it is archive, employment, and ritual boundary.

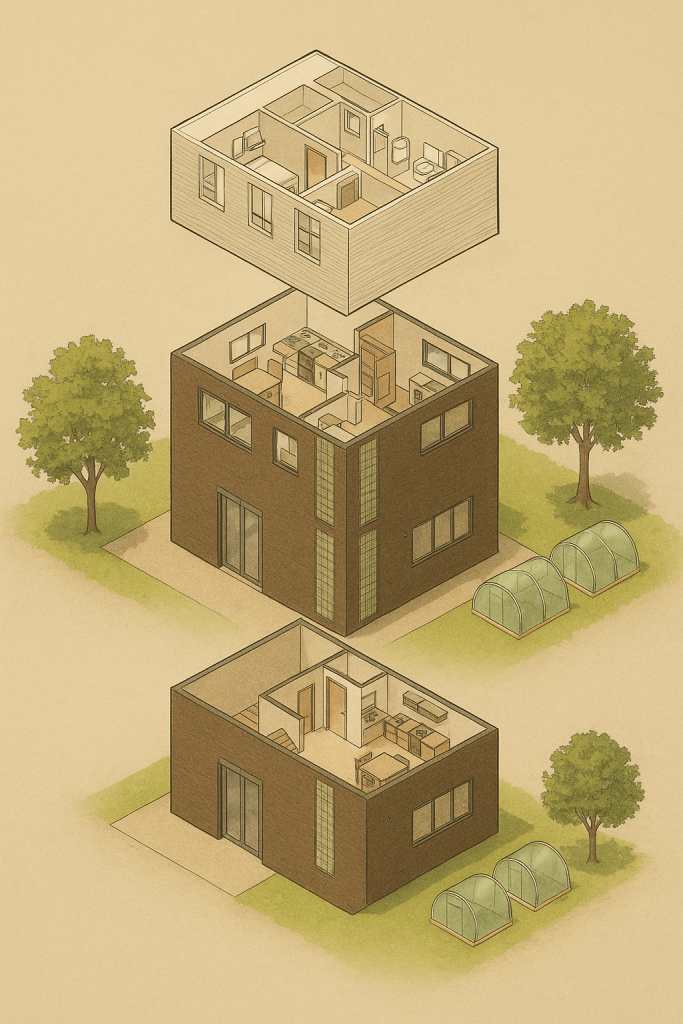

2. Vertical Dignity

Instead of a flattened slab of homogeneity, the building uses staggered vertical massing to create rhythm, presence, and spatial agency.

Each live/work unit is expressed architecturally as a distinct volume, elevating the visual and social identity of the resident.

This spatial gesture says: “Your life is not a number in a spreadsheet. Your corner of the world matters.”

3. Live/Work Autonomy

The unit plans are deliberately configured to interweave domestic and economic life. Each apartment contains a street-facing workspace with its own entrance, signage, and interface with the community. Examples include:

A barber or stylist A traditional healer A trauma-informed therapist A mobile mechanic hub A daycare or doula space

This typology transforms the housing block into a village economy, where financial resilience is not outsourced—but embedded.

4. ADA-First Spatial Justice

Rather than retrofitting accessibility as a compliance task, El Corazón Del Oso is ADA by intention. Every door width, ramp slope, and spatial threshold is a political statement:

That disabled, aging, and mobile-challenged bodies belong here That architectural justice begins with universal access, not marginal accommodation

This principle is extended even into communal gardens, gathering zones, and water infrastructure paths.

5. Water, Sun, and Soil Integration

The systems of the building follow the same logic of empowerment:

Grey water reclamation nourishes food-producing landscapes Rooftop solar arrays generate shared energy for all units Rain gardens and bioswales prevent flooding while inviting nature in On-site composting and tool libraries foster circularity and stewardship

This is not technological sustainability—it is indigenous logic re-encoded into modern form.

Together, these spatial strategies activate a new kind of architecture—not one that imposes form, but one that invites freedom, function, and futurity.

Architecture as Economic Engine

In most affordable housing developments, residents are positioned as recipients of housing, not as producers of wealth. El Corazón Del Oso inverts this paradigm. The architecture is not merely a shelter—it is a self-replicating financial organism, designed to generate long-term economic resilience at the individual, household, and community scale.

1. Live/Work as Foundational Logic

Each unit is structured around the principle that the resident is not just a tenant—but a micro-entrepreneur. The live/work configuration provides:

A dedicated commercial space with visibility and access A physical and legal platform for income generation The ability to scale business activity without leaving the home

This typology decentralizes economic power, making each unit a node of production, not just consumption.

2. Pathways to Ownership

Rather than subject residents to predatory lending or permanent renting, the project introduces:

In-house financing mechanisms at stable, low interest rates Lease-to-own structures that reward long-term residency Equity growth through ownership of income-generating property

By internalizing the mortgage pipeline, El Corazón Del Oso becomes its own bank, disrupting extractive real estate cycles.

3. Localized Labor + Material Economies

The use of compressed earth blocks allows the creation of a neighborhood-scale fabrication industry, training residents to:

Make and sell CEBs for other developments Become skilled tradespeople within the project and beyond Circulate dollars within the community before they leave it

Here, material becomes both shelter and currency.

4. Economic Antifragility

Most housing is vulnerable to inflation, resource shocks, or systemic collapse. El Corazón Del Oso uses its architecture to create economic buffers:

Energy independence through solar microgrid Water security via cistern and reuse systems Food autonomy through garden integration Social capital via shared governance and collective memory

This is a design that does not collapse under stress—it adapts, absorbs, and regrows.

5. Replicability Without Extraction

The model is designed to be replicable across geographies without falling into franchise gentrification. Key elements:

Use of local soil for block production Customization to regional cultural identities Shared equity mechanisms that retain wealth in the community

Architecture, in this context, becomes not a commodity—but a cultural utility.

In El Corazón Del Oso, the walls don’t just protect—they employ, empower, and sustain. This is architecture as infrastructure for sovereignty.

Cultural Semiotics and the Memory of Earth

In El Corazón Del Oso, architecture is not only functional—it is symbolic, ancestral, and ritualistic. Every material decision, spatial rhythm, and formal gesture encodes a deeper message: that to build sustainably is also to remember, and to remember is to restore cultural continuity that centuries of extraction, colonialism, and forced displacement have tried to erase.

1. The Bear as Archetype

The name itself—El Corazón Del Oso (“The Heart of the Bear”)—evokes the mythic and ecological symbolism of the bear:

A creature of protection and maternal strength A symbol of hibernation and awakening—rest and rebirth A land-dweller deeply tied to territory, roots, and seasonal wisdom

The building, like the bear, holds and shelters, inviting cycles of healing, enterprise, and return.

2. Earth as Ancestral Text

By pressing local soil into walls, the project does more than reduce emissions—it reconnects the built environment to the spiritual substrate of land:

Residents inhabit the geology of their place The wall becomes an archive of ancestral resonance Texture, smell, and touch reintroduce a pre-industrial intimacy between body and shelter

This is the antithesis of sheetrock-and-vinyl anonymity. It is a re-indigenization of shelter.

3. Form as Familiar Gesture

The massing, entrances, and porches are arranged not around optimization algorithms, but around cultural rhythm:

Spaces mimic courtyard logics found in Latinx, African, and Indigenous vernaculars Porches are thresholds, not barriers—open invitations to exchange Units are differentiated, not flattened—resisting the “efficiency-as-identity” model

These moves invite users to see themselves in the building—not just as residents, but as inheritors of wisdom.

4. Sacred Zones Within the Everyday

Embedded in the design are ritual-capable spaces:

Niches for altar-building Gathering spaces scaled for song, silence, or intergenerational memory Gardens that grow not just food, but medicine

These are not afterthoughts. They are reparations in form.

5. Architecture as Cultural Continuum

Rather than viewing modern architecture and indigenous form as oppositional, El Corazón Del Oso sees them as entwined:

Technology supports ritual Infrastructure reveals myth Housing becomes hearth

This is not nostalgia—it is cosmology with plumbing. The memory of earth, encoded in space.

Toward a New Ethos of Housing

If El Corazón Del Oso teaches us anything, it is that architecture is never neutral.

Every housing typology encodes a worldview.

Every zoning line, material palette, and funding mechanism is a declaration—of who belongs, who profits, and who endures.

For too long, housing has been designed from the top-down:

by developers optimizing ROI, by policies managing risk, by architects treating residents as “users” rather than co-authors of space.

But housing can be something else.

It can be a civic ceremony.

A cultural inheritance.

A container for sovereignty.

A Model for Replication.

El Corazón Del Oso is not just a one-off. It is a template:

It can be adapted to new bioregions using local soil and solar rhythms It can evolve with different cultural expressions and crafts It can scale without extraction—through cooperatives, land trusts, and participatory ownership models

Wherever displacement and despair take root, the bear may rise.

Conclusion: From Commodity to Cosmology

This project is not simply about bricks and leases.

It is about reprogramming the software of architecture.

It is about designing not only for the body—but for memory, dignity, and future ancestry.

Housing should not just solve for shelter.

It should create the conditions for people to dream again.

“To build the heart of the bear is to remember that shelter is sacred. That land is not a commodity, but a teacher. That our homes can do more than hold us—they can heal us.”

Leave a Reply